Species of Thailand

White-shouldered ibis

Pseudibis davisoni

Allan Octavian Hume, 1875

In Thai: นกช้อนหอยดำ

The white-shouldered ibis is a relatively large ibis species in the family Threskiornithidae. It is native to small regions of Southeast Asia, and is considered to be one of the most threatened bird species of this part of the continent.

Taxonomy and systematics

The white-shouldered ibis was first described by Hume (1875), who originally named the species Geronticus davisoni after his bird collector William Ruxton Davison. Based on this species’ observed similarity with the black ibis (Elliot, 1877), the two species were placed in the same genus. In the more recent past, this ibis has often been classified as a subspecies of the black ibis; but is currently recognised as a separate species.

Description

The adult of this large ibis stands 60–85 cm tall, with males being slightly larger and having slightly longer bills than females. Its only available biometrics are measurements from a single unsexed specimen originating from the 19th century, which include a wing length of 419mm, culmen length of 197mm, tarsus length of 83mm and tail length of 229mm. The plumage is brownish-black, with glossy blue-black wings and tail, and a bare slate-black head which has also been reported as blue or white. A conspicuous neck collar comprising a bluish-white band of bare skin which is broader at the back and narrower at the front extends from the chin around to the nape at the base of the skull. The pale blue is most easily detectable at close range, although this collar has been noted to be completely white in some individuals. The legs are dull red, the iris is orange-red, and the large de-curved bill is yellowish-grey.

The white-shouldered ibis probably owes its name to the clear white observed on the upper part of the neck and chin in some individuals, which may appear as “white shoulders” in flight. In flight, it is also identified by its conspicuous white wing patch, which is visible only as a thin white line when the wings are closed.

The white-shouldered ibis is morphologically similar to its Indian congener the black or red-naped ibis Pseudibis papillosa, but lacks the red tubercles on the nape; and is slightly larger, more robust and has a longer neck and legs. The tail also appears to be shorter and spreads downwards in contrast to straight in the black ibis.

The juvenile has dull-brown plumage along with a tuft of brown feathers on the bluish-white nape, a grey-brown iris, pale yellow legs and dull white feet.

Its vocalisations generally consist of loud, mournful calls that have been described as “weird and unearthly screams”. The hoarse calls of territorial individuals have been described as “errrrh” or “errrrrroh”. It also utters honking screams of “errrrh owk owk owk owk owk” and more subdued “ohhaaa ohhaaa” and “errrrrah”. It makes a loud, harsh “klioh klioh” call during copulation, resembling that of the black woodpecker.

Distribution and habitat

This southeast Asian ibis was once markedly more widespread than presently. The former range extended throughout Southeast Asia from Myanmar to Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and north into Yuman in China. The current population is very small and its distribution highly fragmented; being restricted to northern and eastern Cambodia, southern Vietnam, extreme southern Laos and East Kalimantan.

Cambodia by far forms this species’ stronghold; with 85-95% of the global population of individuals estimated here. The largest known Cambodian white-shouldered ibis subpopulation resides in Western Siem Pang Important Bird Area (minimally 346 individuals). Other sites in Cambodia that hold considerable numbers of white-shouldered ibis include Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary, Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary and the central section of the Mekong River. It is now functionally extinct from Thailand, Myanmar, and southern China; and very scarce in Indonesian Borneo and southern Laos (Birdlife International, 2001).Thailand was once the stronghold for this species, but no official records of its occurrence have been made here since 1937.

The white-shouldered ibis is a lowland specialist and has been found to occur in various habitats including dry dipterocarp forest, margins of seasonal pools (these pools are known locally as “trapaengs”) interspersed within forest, fallow rice fields, shrubby grasslands, forested lake and river margins, gravel and shingle banks at low river levels, sandbanks at wide rivers and, on the Sekong river, sandy islands. At least in Indochina, dry dipterocarp forest seems to be the most important habitat. However, one field study of the local population around the Mekong River in Cambodia found that the ibises nested both in flooded riverine forest and dry inland dipterocarp forest; which was a combination of utilised habitats not observed for any other population.

This species also appears to largely rely on traditional local agriculture to create and maintain its favoured microhabitats, specifically through grazing and trampling of forest vegetation by livestock such as domestic cattle and water buffalo to create clearings as space for preferential foraging habitat; and through wallowing of ungulates in mud to create seasonal pools. This ibis's reliance on human-mediated activity may be especially strong considering both the marked local population declines of many wild ungulates in the white-shouldered ibis's range in the past few decades and the local extinction of many other species such as the Asian elephant; although wild boar may still be important contributors to creating seasonal pools through wallowing. These anthropogenic processes of creating and nurturing suitable habitats may be especially important in the early dry season when such habitat conditions are limited. Anthropogenic burning practices in dipterocarp forest may also have a similar role to grazing for creating suitable clearings.

Feeding

Unlike other sympatric wading birds, the white-shouldered ibis's foraging strategy is notably terrestrial and this bird has not been observed foraging in water. It forages in mud at seasonal pools preferentially covered with short vegetation less than 25 cm high, on the ground in dry dipterocarp forest preferentially with bare underlying substrate, in fallow rice fields, and more occasionally in river channels with large extents of mud and sand. However, it forages almost exclusively at seasonal pools during the breeding season, probably due to high densities of refuge-seeking prey residing between the frequent cracks in the dry mud and hence high availability of food to feed to chicks. With its downcurved bill which has high penetrating power and easy manoeuvrability, the white-shouldered ibis is well adapted to probing into the cracks potentially harbouring these concealed prey. This feeding adaptation in bill morphology gives this ibis an advantage over other sympatric waders with straight bills, and is therefore commonly followed and kleptoparasitised by species such as cattle egrets Numenius arquata and Chinese pond heron Ardeola bacchus. Individuals of this ibis species feed singly, in pairs, or in family groups (flocks of up to 14 being reported); and flock size is notably greater in the wet (non-breeding) season than the dry (non-breeding) season.

Its diet comprises small invertebrates such as large worms, mole crickets, leeches, insect and beetle larvae; amphibians such as Paddy Frogs Feiervarya limnocharis and frogs of Microhyla species; and eels. Although amphibians appear to form the bulk of the diet, the main prey utilised at a given place or time may depend on the texture of the underlying substrate For example, intake rate of invertebrate prey has been found to be significantly higher in saturated than moist or dry grounds; and amphibian intake rate significantly greater in dry than moist, and moist than saturated grounds. However, dry substrate appears to be most profitable to foraging white-shouldered ibises probably due to the high available total biomass constituted by large amphibians (Wright et al. 2013b). Incidentally, there are also unsubstantiated claims of this ibis feeding on fruit.

Occurrence of foraging individuals in forest and field matrix relative to that at pools has been found to increase significantly following rainfall during the wet season, probably due to decreased prey availability at pool margins as amphibian prey taking refuge from desiccation in the mud move into the water, thereby evading foraging ibises. Additionally, swamp eels and crabs which are primarily aquatic and occur in saturated substrate have not been identified in white shouldered-ibis diet because these potential prey could easily evade predation by burrowing or swimming away (Wright et al. 2013b).

Breeding pairs have potentially demanding food requirements, with each pair in Cambodia estimated to utilise nearly two thirds of the total amphibian biomass at a given time for a water hole over an entire breeding season. Therefore, breeding pairs would need to use multiple waterholes for adequate sustenance over the breeding season to avoid prey depletion at one pool, and the supposedly high resultant intraspecific competition would lead to large dispersion of the breeding population. Therefore, any conservation recommendations for this species would need to consider a landscape scale approach.

Breeding

The white-shouldered ibis is a solitary breeder; and in its stronghold of Cambodia, it nests December–April during the mid- to late dry season November – May in dipterocarp tree canopies. This breeding strategy is an exception to the common breeding strategies of sympatric water bird species, which nest in the wet season or from the late wet to mid- dry seasons. However, the white-shouldered ibis's dry-season breeding in Cambodia is probably timed with water drawdown in seasonal pools because of high density of its amphibian prey taking refuge in the cracks in desiccating mud at pool margins; thereby leading to high food availability for chicks and breeding adults. Different breeding seasons have been reported elsewhere in its range; with February–March in Myanmar when it still persisted here, September–December in East Kalimantan, and late August–December in Borneo; with copulation observed in February in this region.

It builds large nests 10-25m aboveground, composed of twigs and fresh leaves, usually in emergent trees such as Koompasia excels as in Borneo. Both partners continue to add nesting material throughout the breeding season and the same nests may be used in successive years. It also more occasionally uses abandoned raptor nests. The clutch contains 2-4 eggs, which are pale blue and hatch asynchronously. The eggs are incubated for 28–31 days by the female. Available reported egg measurements are 61.0-68.2mm in length and 43.9-46.7mm in width. The nestling period from hatching to fledging lasts 26–40 days.

Other behaviour

In contrast to their dry season solitary breeding, white-shouldered ibises become gregarious in the wet season July–October (non-breeding season); when they roost communally in trees. During the wet season, large congregations of white-shouldered ibis (up to 185 individuals at a time have been noted) have also been observed foraging on open terrestrial habitats such as abandoned paddy fields and less frequently at seasonal pools with higher water levels than during the dry season (during breeding).

The white-shouldered ibis is considered sedentary, but some small movements of just over 5 km between roosting and foraging grounds may occur during the wet season. During the wet season in Cambodia, there is considerable movement from pools and wet ground in the dipterocarp forest towards drier forest ground, probably due to easy accessibility of terrestrial invertebrate prey compared to evasive amphibians at the pools. On Borneo, white-shouldered ibises move along large rivers such as the Mahakam in response to large fluctuations in water levels and hence spatiotemporal variations of exposed river banks that serve as suitable feeding grounds. Additionally, large-scale forest fires in East Kalimantan induced by the El Nino Southern Oscillation in the mid-1990s caused large-scale habitat destruction, leading to appreciable movements of individuals into unburnt forest stretches and thereby resulting in a more aggregated local population distribution.

Threats and survival

The white-shouldered ibis is considered one of the most threatened birds of SE Asia. The largest threats to populations of this species are habitat conversion such as wetland drainage for agricultural developments such as plantations, unsustainable rural development, changing land management through land concessions, and infrastructural developments. In the last case for example, the relatively large subpopulations in Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary and at the unprotected section of the Mekong River could be threatened with proposed dams and encroaching human settlement. Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary is also an example region particularly threatened by economic land concessions, through which extensive development could substantially reduce suitable habitat.

The majority of roosting individuals censused in Cambodia (where the largest known populations occur) during the wet season (about three quarters) have been found to occur outside protected areas, revealing an unfortunate spatial mismatch between important roosting sites and these protected areas. This may be because most protected areas are situated far from human settlement; and given the ibis's synanthropic nature (reliant on humans for creating suitable microhabitats), this bird is likely to occur relatively close to settlements; whereby its association with humans may also make it more vulnerable to hunting. Roosting of white shouldered ibises near to or within Economic Land Concessions will likely be severely affected by loss of foraging habitat and human exploitation.

Further, the population at the Mekong River may be particularly vulnerable to human exploitation because the ibis's use of both riverine and dryland forest in this region, thereby potentially exposing it to more human nest exploiters (various workers in the inland forest, and fishers on the river). This ibis may also be in potential competition with humans during amphibian and swamp eel harvesting during the dry season.

Alongside direct habitat loss through land development, the white-shouldered ibis's habitat could also be threatened indirectly through modern agricultural mechanisation to replace traditional keeping of domestic ungulates that graze and trample on underlying vegetation and wallow in mud to maintain forest clearings and seasonal pools as important foraging ground for ibis. The potentially adverse agricultural changes may be driven by the increasing profitability of mechanised farming. The hypothesis concerning the importance of ungulates to ibises in creating suitable habitats has been supported in exclosure experiments which show increased vegetation height and cover in exclosures fenced to bar ungulates compared to unfenced controls. Therefore, the marked decline of traditional farming livelihood practices potentially beneficial to white-shouldered ibis could lead to increased vegetation growth beside pools in clearings, and thereby render these sites unsuitable foraging ground for this ibis. This may be especially likely considering the local extinction or dramatic decline of many wild ungulate species whose role in ibis habitat creation and maintenance has been largely taken over by human-reared ungulates with equivalent functions.

Opportunistic exploitation of nests by humans for food through taking eggs and chicks presents another potential threat. Although human exploitation has been identified as a cause of nest failure, humans are more likely to exploit nests in the late nestling stage; and given that most nest failures have been noted to occur in egg and early nestling stages, natural predation is a more likely cause. Nest guarding schemes in Western Siem Pang have been implemented to investigate chief causes of nest failure, and no significant difference in nest failure has been found between guarded and unguarded control nests; suggesting that natural causes of mortality are more likely. Counterintuitively, conservation interventions to protect nests may disturb the nests so as to increase egg and nestling mortality. Such nest guarding schemes have also faced societal problems.

A potential natural predator of white-shouldered ibis young is the southern jungle crow Corvus macrorhnchos, one individual of which was once observed to remove all eggs of a clutch in the absence of parents, and another of which predated a newly hatched chick. The ibis may also be threatened by mammalian predators such as civets and yellow-throated marten Martes flavigula, although such predators may be more abundant farther from human settlement due to hunting pressure on these mammals. Despite increased likelihood of exploitation of nests closer to settlement, these nests may therefore receive increased indirect protection from predators. Weather poses another potential threat, with some chicks in Cambodia reported as being blown from nests by high winds.

The white-shouldered population on the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan was severely affected by fire damage to forest during an El Nino Southern Oscillation during the mid-1990s. Alongside the primary implication of loss of suitable habitat, the fire may have also led to increased riverbank erosion due to fewer trees, decreased water clarity, and changes in water temperature patterns through fewer overhanging branches; all of which may have affected the birds’ ability to successfully forage on riverbanks and gravel beds.

In relation with humans

Given this species large apparent reliance on human agricultural activity (both traditional arable and pastoral) to maintain its habitats, it may found relatively closer to human habitation than similar sympatric species such as the giant ibis; and may even roost and nest in trees near to rice paddies even when in use by people. However, this ibis is more likely more attracted to the agricultural foraging grounds close to human habitation rather than humans per se. Although the white-shouldered ibis is exploited opportunistically by humans for food, it is not commercially valued for trade.

The only captive record for this species is for one specimen that was imported into Thailand from Cambodia in 1989, and held at the Queen's Bird Park at Ayuthhaya near Bangkok in 1990.

Status

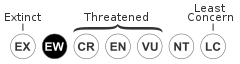

Populations of the white-shouldered ibis declined severely late in the 20th century; and given the scarcity of recorded sightings in the past few decades, the small population size and persistent habitat loss, it has been classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN. The global population is estimated at 1000 individuals, an estimated 670 of which are mature. 973 individuals were counted in a nationwide population census in Cambodia in 2013, whereas 30-100 individuals are estimated for the Indonesian portion of the species’ range.

Etymology

The binomial commemorates William Ruxton Davison.

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Category / Seasonal Status

Wiki listed status (concerning Thai population): Extirpated, critically endangered

BCST Category: Not recorded in wild in last 50 years

BCST Seasonal statuses:

- Resident or presumed resident

- Extirpated

Site notes

This species is extirpared in Thailand.

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Subphylum

- Vertebrata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Pelecaniformes

- Family

- Threskiornithidae

- Genus

- Pseudibis

- Species

- Pseudibis davisoni

Common names

- Thai: นกช้อนหอยดำ

Synonyms

- Pseudibis papillosa davisoni

Conservation status

Critically Endangered (IUCN3.1)

Critically Endangered (BirdLife)

Extinct in the Wild (ONEP)

Extinct in the Wild (BCST)

Photos

Range Map