Species of Thailand

Reticulated python

Malayopython reticulatus

(Johann Gottlob Schneider, 1801)

In Thai: งูเหลือม, ngu luam

The reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) is a python species native to South and Southeast Asia. It is the world's longest snake, and the third heaviest after the green anaconda and Burmese python. It is listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List because of its wide distribution. In several countries in its range, it is hunted for its skin, for use in traditional medicine, and for sale as pets. Due to this, reticulated pythons are one of the most economically important reptiles worldwide.

It is an excellent swimmer, has been reported far out at sea, and has colonized many small islands within its range.

Like all pythons, it is a non-venomous constrictor. In very rare cases, adult humans have been killed (and in at least three reported cases, eaten) by reticulated pythons.

Taxonomy

The reticulated python was first described in 1801 by German naturalist Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider, who described two zoological specimens held by the Göttingen Museum in 1801 that differed slightly in colour and pattern as separate species—Boa reticulata and Boa rhombeata. The specific name, reticulatus, is Latin meaning "net-like", or , and is a reference to the complex color pattern. The generic name Python was proposed by French naturalist François Marie Daudin in 1803. American zoologist Arnold G. Kluge performed a cladistics analysis on morphological characters and recovered the reticulated python lineage as sister to the genus Python, hence not requiring a new generic name in 1993.

In a 2004 genetics study using cytochrome b DNA, and colleagues discovered the reticulated python as sister to Australo-Papuan pythons, rather than Python molurus and relatives. Raymond Hoser erected the genus Broghammerus for the reticulated python in 2004, naming it after German snake expert Stefan Broghammer, on the basis of dorsal patterns distinct from those of the genus Python, and a dark mid-dorsal line from the rear to the front of the head, and red or orange (rather than brown) iris colour. In 2008, Lesley H. Rawlings and colleagues reanalysed Kluge's morphological data and combined it with genetic material, finding the reticulated clade to be an offshoot of the Australo-Papuan lineage as well. They adopted and redefined the genus name Broghammerus.

Most taxonomists choose to ignore Broghammerus and other names by Hoser as its description lacked scientific rigour and was not published in a reputable journal. and colleagues accordingly proposed the name Malayopython for this species and its sister species, the Timor python. Malayopython has been recognized by subsequent authors and the Reptile Database. Hoser has argued that Broghammerus was validly published and Malayopython name is invalid as it is a junior synonym. In 2021, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature found no basis for regarding the name Broghammerus to be invalid. Nevertheless, the name Malayopython remains in use by reliable sources.

Subspecies

Three subspecies have been proposed:

- M. r. reticulatus (Schneider, 1801) – Asian reticulated python

- M. r. jampeanus et al., 2002 – Kayaudi reticulated python or Tanahjampean reticulated python, about half the length, or according to Auliya et al. (2002), not reaching much more than 2 m ftin in length. Found on Tanahjampea in the Selayar Archipelago south of Sulawesi. Closely related to M. r. reticulatus of the Lesser Sundas.

- M. r. saputrai Auliya et al., 2002 – Selayer reticulated python, occurs on Selayar Island in the Selayar Archipelago and also in adjacent Sulawesi. This subspecies represents a sister lineage to all other populations of reticulated pythons tested. According to Auliya et al. (2002) it does not exceed 4 m ftin in length.

The latter two are dwarf subspecies. Apparently, the population of the Sangihe Islands north of Sulawesi represents another such subspecies, which is basal to the P. r. reticulatus plus P. r. jampeanus clade, but it is not yet formally described.

The proposed subspecies M. r. "dalegibbonsi", M. r. "euanedwardsi", M. r. "haydnmacphiei", M. r. "neilsonnemani", M. r. "patrickcouperi", and M. r. "stuartbigmorei" have not found general acceptance.

Characteristics

The reticulated python has smooth dorsal scales that are arranged in 69–79 rows at midbody. Deep pits occur on four anterior upper labials, on two or three anterior lower labials, and on five or six posterior lower labials.

The reticulated python is the largest snake native to Asia. More than a thousand wild reticulated pythons in southern Sumatra were studied, and estimated to have a length range of 1.5 to 6.5 m ftin, and a weight range of 1 to 75 kg lboz. Reticulated pythons with lengths more than 6 m ftin are rare, though according to the Guinness Book of World Records, it is the only extant snake to regularly exceed that length. One of the largest scientifically measured specimens, from Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, was measured under anesthesia at 6.95 m ftin and weighed 59 kg lboz after not having eaten for nearly 3 months.

The specimen once widely accepted as the largest-ever "accurately" measured snake, that being Colossus, a specimen kept at the Highland Park Zoo (now the Pittsburgh Zoo and Aquarium) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, during the 1950s and early 1960s, with a peak reported length of 8.7 m ftin from a measurement in November 1956, was later shown to have been substantially shorter than previously reported. When Colossus died on 14 April 1963, its body was deposited in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. At that time, its skeleton was measured and found to be 6.35 m in total length, and the length of its fresh hide was measured as 7.29 m. The hide tends to stretch from the skinning process, thus may be longer than the snake from which it came – e.g., by roughly 20–40% or more. The previous reports had been constructed by combining partial measurements with estimations to compensate for "kinks", since completely straightening an extremely large live python is virtually impossible. Because of these issues, a 2012 journal article concluded, "Colossus was neither the longest snake nor the heaviest snake ever maintained in captivity." Too large to be preserved with formaldehyde and then stored in alcohol, the specimen was instead prepared as a disarticulated skeleton. The hide was sent to a laboratory to be tanned, but it was either lost or destroyed, and now only the skull and selected vertebrae and ribs remain in the museum's collection. Considerable confusion exists in the literature over whether Colossus was male or female (females tend to be larger).

Numerous reports have been made of larger snakes, but since none of these was measured by a scientist nor any of the specimens deposited at a museum, they must be regarded as unproven and possibly erroneous. In spite of what has been, for many years, a standing offer of a large financial reward (initially $1, 000, later raised to $5, 000, then $15, 000 in 1978 and $50, 000 in 1980) for a live, healthy snake 9.14 m or longer by the New York Zoological Society (later renamed as the Wildlife Conservation Society), no attempt to claim this reward has ever been made.

The colour pattern is a complex geometric pattern that incorporates different colours. The back typically has a series of irregular diamond shapes flanked by smaller markings with light centers. In this species' wide geographic range, much variation of size, colour, and markings commonly occurs.

In zoo exhibits, the colour pattern may seem garish, but in a shadowy jungle environment amid fallen leaves and debris, it allows them to virtually disappear. Called disruptive colouration, it protects them from predators and helps them to catch their prey.

The huge size and attractive pattern of this snake has made it a favorite zoo exhibit, with several individuals claimed to be above 20 m in length and more than one claimed to be the largest in captivity. However, due to its huge size, immense strength, aggressive disposition, and the mobility of the skin relative to the body, it is very difficult to get exact length measurements of a living reticulated python, and weights are rarely indicative, as captive pythons are often obese. Claims made by zoos and animal parks are sometimes exaggerated, such as the claimed 14.85 m ftin snake in Indonesia which was subsequently proven to be about 6.5 - 7 m ftin long. For this reason, scientists do not accept the validity of length measurements unless performed on a dead or anesthetized snake that is later preserved in a museum collection or stored for scientific research.

A reticulated python kept in the United States in Kansas City, Missouri, named "Medusa" is considered by the Guinness Book of World Records to be the longest living snake ever kept in captivity. In 2011 it was reported to measure 7.67 m ftin and weigh 158.8 kg lboz.

In 2012, an albino reticulated python, named "Twinkie", housed in Fountain Valley, California, was considered to be the largest albino snake in captivity by the Guinness World Records. It measured 7 m ftin in length and weighed about 168 kg.

Dwarf forms of reticulated pythons also occur, from some islands northwest of Australia, and these are being selectively bred in captivity to be much smaller, resulting in animals often referred to as "super dwarfs". Adult super dwarf reticulated pythons are typically between 1.82 and 2.4 m ftin in length.

Distribution and habitat

The reticulated python is found in South and Southeast Asia from the Nicobar Islands, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore, east through Indonesia and the Indo-Australian Archipelago (Sumatra, the Mentawai Islands, the Natuna Islands, Borneo, Sulawesi, Java, Lombok, Sumbawa, Sumba, Flores, Timor, Maluku, Tanimbar Islands) and the Philippines (Basilan, Bohol, Cebu, Leyte, Luzon, Mindanao, Mindoro, Negros, Palawan, Panay, Polillo, Samar, Tawi-Tawi). The original description does not include a type locality. The type locality was restricted to "Java" by Brongersma (1972).

Three subspecies have been proposed, but are not recognized in the Integrated Taxonomic Information System. The color and size can vary a great deal among the subspecies described. Geographical location is a good key to establishing the subspecies, as each one has a distinct geographical range.

The reticulated python lives in rainforests, woodlands, and nearby grasslands. It is also associated with rivers and is found in areas with nearby streams and lakes. An excellent swimmer, it has even been reported far out at sea and has consequently colonized many small islands within its range. During the early years of the 20th century, it is said to have been common even in busy parts of Bangkok, sometimes eating domestic animals.

Diet

As with all pythons, the reticulated python is an ambush predator, usually waiting until prey wanders within strike range before seizing it in its coils and killing by constriction. Its natural diet includes mammals and occasionally birds. Small specimens up to 3 - 4 m ftin long eat mainly small mammals such as rats, other rodents, mouse-eared bats, and treeshrews, whereas larger individuals switch to prey such as small Indian civet and binturong, primates, pigs, and deer weighing more than 60 kg lboz. As a rule, the reticulated python seems able to swallow prey up to one-quarter its own length and up to its own weight. Near human habitation, it is known to snatch stray chickens, cats, and dogs on occasion.

Among the largest documented prey items are a half-starved sun bear of 23 kg lboz that was eaten by a 6.95 m adj=on ftin specimen and took some 10 weeks to digest.

At least one case is reported of a foraging python entering a forest hut and taking a child.

Reproduction

The reticulated python is oviparous. Adult females lay between 15 and 80 eggs per clutch. At an optimum incubation temperature of 31-32 C, the eggs take an average of 88 days to hatch. Hatchlings are at least 2 order=flip in length.

Danger to humans

The reticulated python is among the few snakes that prey on humans. In 2015, the species was added to the Lacey Act of 1900, prohibiting import and interstate transport due to its "injurious" history with humans. Attacks on humans are not common, but this species has been responsible for several reported human fatalities, in both the wild and captivity. Considering the known maximum prey size, a full-grown reticulated python can open its jaws wide enough to swallow a human, but the width of the shoulders of some adult Homo sapiens can pose a problem for even a snake with sufficient size. Reports of human fatalities and human consumption (the latest examples of consumption of an adult human being well authenticated) include:

- A report of a visit of Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East India Company, to the Banda Islands in 1638, includes a description of an enslaved woman who, when tending to a garden on the volcanic island of Gunung Api, was strangled by a snake of "24 houtvoeten" (slightly over seven meters) in length, and then swallowed whole. The snake, having become slow after ingesting such a large prey, was subsequently shot by Dutch soldiers and brought to the Governor-General to be looked at, with its victim still inside. Although less reliable than this first-hand document, several early published travel journals describe similar episodes.

- In early 20th-century Indonesia: On Salibabu island, North Sulawesi, a 14-year-old boy was killed and supposedly eaten by a specimen 5.17 m in length. Another incident involved a woman reputedly eaten by a "large reticulated python", but few details are known.

- In the early 1910s or in 1927, a jeweller went hunting with his friends and was apparently eaten by a 6 m python after he sought shelter from a rainstorm in or under a tree. Supposedly, he was swallowed feet-first, perhaps the easiest way for a snake to actually swallow a human.

- Among a small group of Aeta peoples in the Philippines, six deaths by pythons were said to have been documented within a period of 40 years, plus one who died later of an infected bite.

- In September 1995, a 29-year-old rubber tapper from the southern Malaysian state of Johor was reported to have been killed by a large reticulated python. The victim had apparently been caught unaware and was squeezed to death. The snake had coiled around the lifeless body with the victim's head gripped in its jaws when it was stumbled upon by the victim's brother. The python, reported as measuring 7 m long and weighing more than 140 kg, was killed soon after by the arriving police, who shot it four times.

- In October 2008, a 25-year-old woman from Virginia Beach appeared to have been killed by a 4 m pet reticulated python. The apparent cause of death was asphyxiation. The snake was later found in the bedroom in an agitated state.

- In January 2009, a 3-year-old boy was wrapped in the coils of a 18 pet reticulated python, turning blue. The boy's mother, who had been petsitting the python on behalf of a friend, rescued him by gashing the python with a knife. The snake was later euthanized because of its wounds.

- In December 2013, a 59-year-old security guard was strangled to death while trying to capture a python near the Bali Hyatt, a luxury hotel on Indonesia's resort island. The incident happened around 3 am as the 4.5-m (15-ft) python was crossing a road near the hotel. The victim had offered to help capture the snake, which had been spotted several times before near the hotel in the Sanur, Bali, area and escaped back into nearby bushes.

- In March 2017, the body of Akbar Salubiro, a 25-year-old farmer in Central Mamuju Regency, West Sulawesi, Indonesia, was found inside the stomach of a 7 m reticulated python. He had been declared missing from his palm tree plantation, and the people searching for him found the python the next day with a large bulge in its stomach. They killed the python and found the whole body of the missing farmer inside. This was the first fully confirmed case of a person being eaten by a python. The process of retrieving the body from the python's stomach was documented by pictures and videos taken by witnesses.

- In June 2018, a 54-year-old Indonesian woman in Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, was killed and eaten by a 7 m python. The woman went missing one night while working in her garden, and the next day, a search party was organized after some of her belongings were found abandoned in the garden. The python was found near the garden with a large bulge in its body. The snake was killed and carried into town, where it was cut open, revealing the woman's body completely intact.

- In June 2020, a 16-year-old Indonesian boy was attacked and killed by a 7 m long python in Bombana Regency, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. The incident took place near a waterfall at Mount Kahar in Rumbia sub-district. The victim was separated from his four friends in the woods. When he screamed, his friends came to help and found him encoiled by a large python. Villagers came to help and managed to kill the snake using a parang machete. However, the victim had already suffocated.

- In October 2022, a 52-year-old woman in Terjun Gajah village, Betara Subdistrict, West Tanjung Jabung Regency, Jambi, Indonesia, was killed and swallowed whole by a 6 m reticulated python. She went to tap rubber sap on 23 October 2022 and did not return home after sunset. After she was reported missing for a day and a night, a search party discovered a large python with a bulge in its body in a jungle near the rubber plantation. The villagers immediately killed and dissected the python and discovered the intact body of the missing woman inside. Villagers eared more large pythons might be present because farmers previously had reported two goats missing.

In captivity

Increased popularity of the reticulated python in the pet trade is due largely to increased efforts in captive breeding and selectively bred mutations such as the "albino" and "tiger" strains. Smaller variants such as the "super dwarf" variants found on small islands are likewise popular due to their smaller size, as they grow to a fraction of the lengths and weights of their mainland kin due to genetics, limited space and prey availability. It can make a good captive, but keepers working with adults from mainland populations should have previous experience with large constrictors to ensure safety to both animal and keeper. Although its interactivity and beauty draws much attention, some feel it is unpredictable. The python can bite and possibly constrict if it feels threatened, or mistakes a hand for food. While not venomous, large pythons can inflict serious injuries by biting, sometimes requiring stitches.

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Subphylum

- Vertebrata

- Class

- Reptilia

- Order

- Squamata

- Suborder

- Serpentes

- Family

- Pythonidae

- Genus

- Malayopython

- Species

- Malayopython reticulatus

Common names

- German: Netzpython

- English: Reticulated python

- Thai: งูเหลือม, ngu luam

Subspecies

Python reticulatus jampeanus, Mark Auliya et al., 2002

Python reticulatus reticulatus, Johann Gottlob Schneider, 1801

Python reticulatus saputrai, Mark Auliya et al., 2002

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN3.1)

Photos

Please help us review our species pages if wrong photos are used or any other details in the page is wrong. We can be reached via our contact us page.

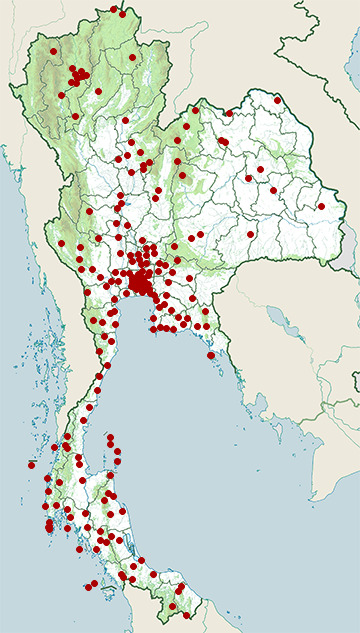

Range Map

- Ao Luek District, Krabi

- Ban Bueng District, Chonburi

- Ban Chang District, Rayong

- Ban Lat District, Phetchaburi

- Ban Mo District, Saraburi

- Ban Na District, Nakhon Nayok

- Ban Pong District, Ratchaburi

- Bang Bo District, Samut Prakan

- Bang Bua Thong District, Nonthaburi

- Bang Kapi District, Bangkok

- Bang Khae District, Bangkok

- Bang Khen District, Bangkok

- Bang Lamung District, Chonburi

- Bang Lang National Park

- Bang Len District, Nakhon Pathom

- Bang Pa In District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Bang Pahan District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Bang Pakong District, Chachoengsao

- Bang Phlat District, Bangkok

- Bang Phli District, Samut Prakan

- Bang Rakam District, Phitsanulok

- Bang Sao Thong District, Samut Prakan

- Bang Saphan District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Bang Yai District, Nonthaburi

- Bangkok Province

- Bangkok Noi District, Bangkok

- Budo - Su-ngai Padi National Park

- Bueng Kum District, Bangkok

- Bueng Sam Phan District, Phetchabun

- Cha-Am District, Phetchaburi

- Chaiya District, Surat Thani

- Chaloem Phra Kiat District, Saraburi

- Chiang Saen District, Chiang Rai

- Chom Thong District, Bangkok

- Chom Thong District, Chiang Mai

- Dan Chang District, Suphan Buri

- Doem Bang Nang Buat District, Suphan Buri

- Doi Saket District, Chiang Mai

- Don Mueang District, Bangkok

- Erawan National Park

- Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary

- Hat Yai District, Songkhla

- Hua Hin District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

- Huai Khwang District, Bangkok

- Huai Yot District, Trang

- Kabin Buri District, Prachinburi

- Kaeng Krachan District, Phetchaburi

- Kaeng Krachan National Park

- Kamphaeng Saen District, Nakhon Pathom

- Kantang District, Trang

- Kantharawichai District, Maha Sarakham

- Kao Liao District, Nakhon Sawan

- Kathu District, Phuket

- Khan Na Yao District, Bangkok

- Khanom District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Chamao - Khao Wong National Park

- Khao Lampi - Hat Thai Mueang National Park

- Khao Luang National Park

- Khao Nan National Park

- Khao Phanom District, Krabi

- Khao Phra - Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Soi Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Sok National Park

- Khao Yai Da

- Khao Yai National Park

- Khlong Luang District, Pathum Thani

- Khlong San District, Bangkok

- Khuan Don District, Satun

- Klaeng District, Rayong

- Ko Chang District, Trat

- Ko Chang (South Thailand)

- Ko Chang National Park

- Ko Lanta National Park

- Ko Lipe

- Ko Pha Ngan

- Ko Pha-ngan District, Surat Thani

- Ko Phra Thong

- Ko Samui District, Surat Thani

- Ko Tao

- Krasang District, Buriram

- Krok Phra District, Nakhon Sawan

- Kui Buri National Park

- La-un District, Ranong

- Lam Luk Ka District, Pathum Thani

- Lat Krabang District, Bangkok

- Li District, Lamphun

- Mae On District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Rim District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai

- Makham District, Chanthaburi

- Mueang Chiang Mai District, Chiang Mai

- Mueang Chonburi District, Chonburi

- Mueang Chumphon District, Chumphon

- Mueang Kalasin District, Kalasin

- Mueang Kanchanaburi District, Kanchanaburi

- Mueang Krabi District, Krabi

- Mueang Lampang District, Lampang

- Mueang Lamphun District, Lamphun

- Mueang Loei District, Loei

- Mueang Lopburi District, Lopburi

- Mueang Nakhon Nayok District, Nakhon Nayok

- Mueang Nakhon Pathom District, Nakhon Pathom

- Mueang Nakhon Ratchasima District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Mueang Nakhon Sawan District, Nakhon Sawan

- Mueang Nong Khai District, Nong Khai

- Mueang Nonthaburi District, Nonthaburi

- Mueang Pathum Thani District, Pathum Thani

- Mueang Phang Nga District, Phang Nga

- Mueang Phatthalung District, Phatthalung

- Mueang Phetchaburi District, Phetchaburi

- Mueang Phichit District, Phichit

- Mueang Phitsanulok District, Phitsanulok

- Mueang Phuket District, Phuket

- Mueang Prachinburi District, Prachinburi

- Mueang Prachuap Khiri Khan District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Mueang Rayong District, Rayong

- Mueang Samut Prakan District, Samut Prakan

- Mueang Samut Sakhon District, Samut Sakhon

- Mueang Saraburi District, Saraburi

- Mueang Songkhla District, Songkhla

- Mueang Suphanburi District, Suphan Buri

- Mueang Trang District, Trang

- Mueang Uttaradit District, Uttaradit

- Na Yong District, Trang

- Nam Nao National Park

- Ngao Waterfall National Park

- Noen Maprang District, Phitsanulok

- Nong Khaem District, Bangkok

- Nong Phai District, Phetchabun

- Nong Wua So District, Udon Thani

- Nong Yai District, Chonburi

- Ongkharak District, Nakhon Nayok

- Pai District, Mae Hong Son

- Pak Chom District, Loei

- Pak Chong District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Pak Kret District, Nonthaburi

- Pak Phanang District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Pathio District, Chumphon

- Phachi District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Phak Hai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Phanat Nikhom District, Chonburi

- Phato District, Chumphon

- Phi Phi Islands

- Photharam District, Ratchaburi

- Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakan

- Phu Foi Lom National Park

- Phu Khiao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phu Luang Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phu Wua Wildlife Sanctuary

- Phuket Province

- Phunphin District, Surat Thani

- Pong District, Phayao

- Pran Buri District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Prawet District, Bangkok

- Ratchasan District, Chachoengsao

- Ron Phibun District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Rueso District, Narathiwat

- Sadao District, Songkhla

- Sai Mai District, Bangkok

- Sai Noi District, Nonthaburi

- Sai Yok District, Kanchanaburi

- Samut Songkhram Province

- San Kamphaeng District, Chiang Mai

- San Pa Tong District, Chiang Mai

- Saphan Sung District, Bangkok

- Sapphaya District, Chainat

- Saraphi District, Chiang Mai

- Sattahip District, Chonburi

- Sena District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Si Banphot District, Phatthalung

- Si Racha District, Chonburi

- Si Sawat District, Kanchanaburi

- Suan Luang District, Bangkok

- Suan Phueng District, Ratchaburi

- Sung Noen District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Surin Islands

- Takua Pa District, Phang Nga

- Tarutao National Marine Park

- Tha Chana District, Surat Thani

- Tha Mai District, Chanthaburi

- Tha Muang District, Kanchanaburi

- Tha Sala District, Nakhon Si Thammarat

- Thalang District, Phuket

- Thale Ban National Park

- Tham Pha Tha Phon Non-Hunting Area

- Thanyaburi District, Pathum Thani

- Thap Sakae District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Thawi Watthana District, Bangkok

- Thepha District, Songkhla

- Thong Pha Phum District, Kanchanaburi

- Thung Khao Luang District, Roi Et

- Thung Khru District, Bangkok

- Thung Salaeng Luang National Park

- Trakan Phuet Phon District, Ubon Ratchathani

- Wang Chan District, Rayong

- Wang Noi District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Wang Thong District, Phitsanulok

- Wat Bot District, Phitsanulok

- Wat Sing District, Chainat