Species of Thailand

Eurasian hoopoe

Upupa epops

Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

In Thai: นกกะรางหัวขวาน

Hoopoes are colourful birds found across Africa, Asia, and Europe, notable for their distinctive "crown" of feathers. Three living and one extinct species are recognised, though for many years all of the extant species were lumped as a single species—Upupa epops. In fact, some taxonomists still consider all three species conspecific. Some authorities also keep the African and Eurasian hoopoe together, but split the Madagascar hoopoe.

Taxonomy and systematics

Upupa and epops are respectively the Latin and Ancient Greek names for the hoopoe; both, like the English name, are onomatopoeic forms which imitate the cry of the bird.

The hoopoe was classified in the clade Coraciiformes, which also includes kingfishers, bee-eaters, and rollers. A close relationship between the hoopoe and the wood hoopoes is also supported by the shared and unique nature of their stapes. In the Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy, the hoopoe is separated from the Coraciiformes as a separate order, the Upupiformes. Some authorities place the wood hoopoes in the Upupiformes as well. Now the consensus is that both hoopoe and the wood hoopoes belong with the hornbills in the Bucerotiformes.

The fossil record of the hoopoes is very incomplete, with the earliest fossil coming from the Quaternary. The fossil record of their relatives is older, with fossil wood hoopoes dating back to the Miocene and those of an extinct related family, the Messelirrisoridae, dating from the Eocene.

Species

Formerly considered a single species, the hoopoe has been split into three separate species: the Eurasian hoopoe, Madagascan hoopoe and the resident African hoopoe. One accepted separate species, the Saint Helena hoopoe, lived on the island of St Helena but became extinct in the 16th century, presumably due to introduced species.

The genus Upupa was created by Linnaeus in his Systema naturae in 1758. It then included three other species with long curved bills:

- U. eremita (now Geronticus eremita), the northern bald ibis

- U. pyrrhocorax (now Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), the red-billed chough

- U. paradisea

Formerly, the greater hoopoe-lark was also considered to be a member of this genus (as Upupa alaudipes).

Extant species

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upupa africana | African hoopoe | South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Angola, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Saudi Arabia and the southern half of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| Upupa epops | Eurasian hoopoe | Europe, Asia, and North Africa and northern Sub-Saharan Africa | |

| Upupa marginata | Madagascan hoopoe | Madagascar | |

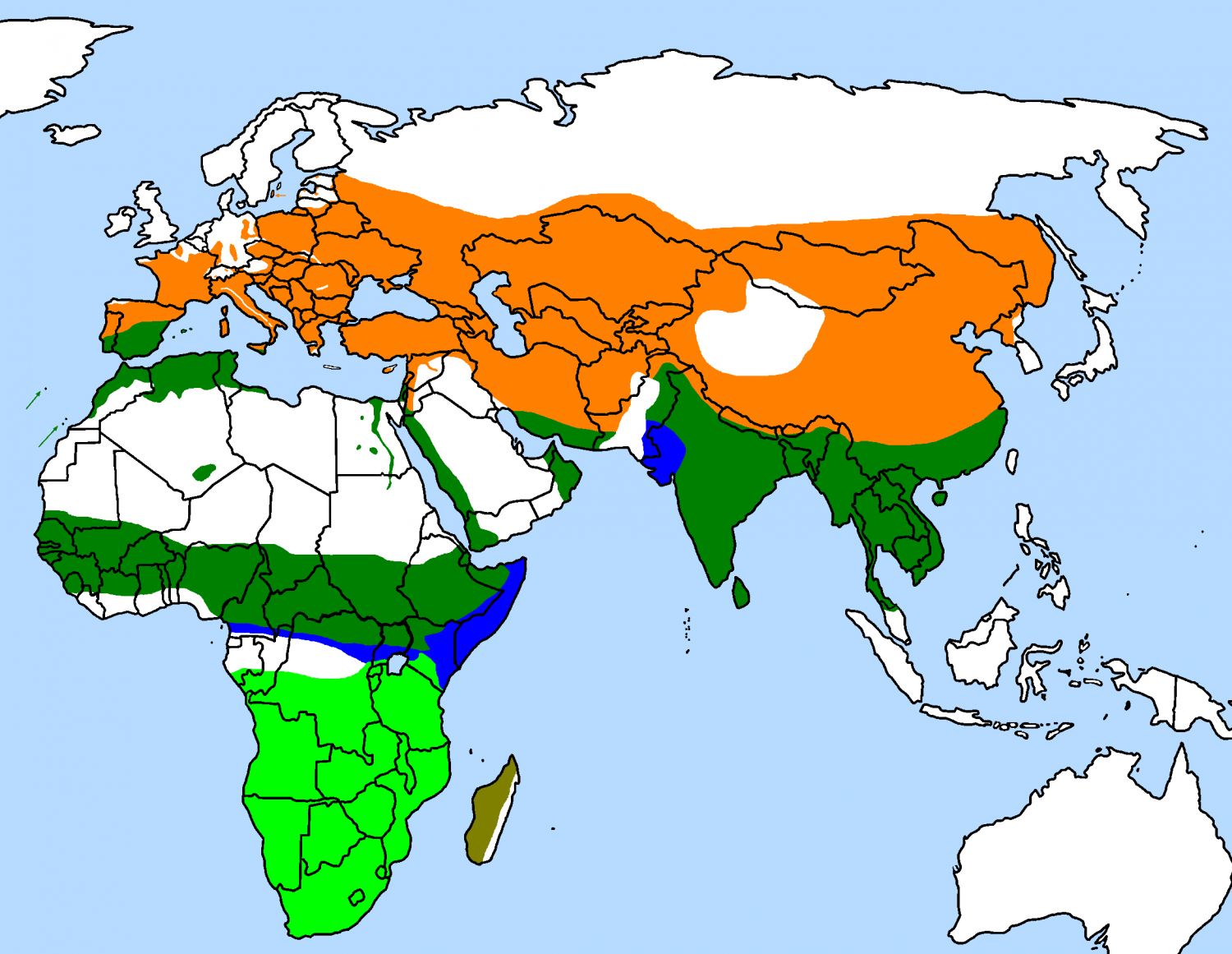

Distribution and habitat

Hoopoes are widespread in Europe, Asia, and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. Most European and north Asian birds migrate to the tropics in winter. In contrast, the African populations are sedentary all year. The species has been a vagrant in Alaska; U. e. saturata was recorded there in 1975 in the Yukon Delta. Hoopoes have been known to breed north of their European range, and in southern England during warm, dry summers that provide plenty of grasshoppers and similar insects, although as of the early 1980s northern European populations were reported to be in the decline, possibly due to changes in climate.

The hoopoe has two basic requirements of its habitat: bare or lightly vegetated ground on which to forage and vertical surfaces with cavities (such as trees, cliffs or even walls, nestboxes, haystacks, and abandoned burrows) in which to nest. These requirements can be provided in a wide range of ecosystems, and as a consequence the hoopoe inhabits a wide range of habitats such as heathland, wooded steppes, savannas and grasslands, as well as forest glades. The Madagascar subspecies also makes use of more dense primary forest. The modification of natural habitats by humans for various agricultural purposes has led to hoopoes becoming common in olive groves, orchards, vineyards, parkland and farmland, although they are less common and are declining in intensively farmed areas. Hunting is of concern in southern Europe and Asia.

Hoopoes make seasonal movements in response to rain in some regions such as in Ceylon and in the Western Ghats. Birds have been seen at high altitudes during migration across the Himalayas. One was recorded at about 6400 m by the first Mount Everest expedition.

Behaviour and ecology

In what was long thought to be a defensive posture, hoopoes sunbathe by spreading out their wings and tail low against the ground and tilting their head up; they often fold their wings and preen halfway through. They also enjoy taking dust and sand baths. Adults may begin their moult after the breeding season and continue after they have migrated for the winter.

Diet and feeding

The diet of the hoopoe is mostly composed of insects, although small reptiles, frogs and plant matter such as seeds and berries are sometimes taken as well. It is a solitary forager which typically feeds on the ground. More rarely they will feed in the air, where their strong and rounded wings make them fast and manoeuverable, in pursuit of numerous swarming insects. More commonly their foraging style is to stride over relatively open ground and periodically pause to probe the ground with the full length of their bill. Insect larvae, pupae and mole crickets are detected by the bill and either extracted or dug out with the strong feet. Hoopoes will also feed on insects on the surface, probe into piles of leaves, and even use the bill to lever large stones and flake off bark. Common diet items include crickets, locusts, beetles, earwigs, cicadas, ant lions, bugs and ants. These can range from 10 to 150 mm in length, with a preferred prey size of around 20 – 30 mm. Larger prey items are beaten against the ground or a preferred stone to kill them and remove indigestible body parts such as wings and legs.

Breeding

Hoopoes are monogamous, although the pair bond apparently only lasts for a single season. They are also territorial. The male calls frequently to advertise his ownership of the territory. Chases and fights between rival males (and sometimes females) are common and can be brutal. Birds will try to stab rivals with their bills, and individuals are occasionally blinded in fights. The nest is in a hole in a tree or wall, and has a narrow entrance. It may be unlined, or various scraps may be collected. The female alone is responsible for incubating the eggs. Clutch size varies with location: Northern Hemisphere birds lay more eggs than those in the Southern Hemisphere, and birds at higher latitudes have larger clutches than those closer to the equator. In central and northern Europe and Asia the clutch size is around 12, whereas it is around four in the tropics and seven in the subtropics. The eggs are round and milky blue when laid, but quickly discolour in the increasingly dirty nest. They weigh 4.5 g. A replacement clutch is possible.

Hoopoes have well-developed anti-predator defences in the nest. The uropygial gland of the incubating and brooding female is quickly modified to produce a foul-smelling liquid, and the glands of nestlings do so as well. These secretions are rubbed into the plumage. The secretion, which smells like rotting meat, is thought to help deter predators, as well as deter parasites and possibly act as an antibacterial agent. The secretions stop soon before the young leave the nest. From the age of six days, nestlings can also direct streams of faeces at intruders, and will hiss at them in a snake-like fashion. The young also strike with their bill or with one wing.

The incubation period for the species is between 15 and 18 days, during which time the male feeds the female. Incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid, so the chicks are born asynchronously. The chicks hatch with a covering of downy feathers. By around day three to five, feather quills emerge which will become the adult feathers. The chicks are brooded by the female for between 9 and 14 days. The female later joins the male in the task of bringing food. The young fledge in 26 to 29 days and remain with the parents for about a week more.

Relationship with humans

The diet of the hoopoe includes many species considered by humans to be pests, such as the pupae of the processionary moth, a damaging forest pest. For this reason the species is afforded protection under the law in many countries.

Hoopoes are distinctive birds and have made a cultural impact over much of their range. They were considered sacred in Ancient Egypt, and were "depicted on the walls of tombs and temples". At the Old Kingdom, the hoopoe was used in the iconography as a symbolic code to indicate the child was the heir and successor of his father. They achieved a similar standing in Minoan Crete.

In the Torah, Leviticus 11:13–19, hoopoes were listed among the animals that are detestable and should not be eaten. They are also listed in Deuteronomy as not kosher.

Hoopoes also appear in the Quran and is known as the "hudhud", in Surah Al-Naml 27:20–24: "And he took attendance of the birds and said, "Why do I not see the hoopoe - or is he among the absent? (20) I will surely punish him with a severe punishment or slaughter him unless he brings me clear authorization." (21) But the hoopoe stayed not long and said, "I have encompassed that which you have not encompassed, and I have come to you from Sheba with certain news. (22) Indeed, I found a woman ruling them, and she has been given of all things, and she has a great throne. (23) I found her and her people prostrating to the sun instead of Allah, and Satan has made their deeds pleasing to them and averted them from way, so they are not guided, (24)".

The sacredness of the Hoopoe and connection with Solomon and the Queen of Sheba is mentioned in passing in Rudyard Kipling's "The Butterfly that Stamped."

Hoopoes were seen as a symbol of virtue in Persia. A hoopoe was a leader of the birds in the Persian book of poems The Conference of the Birds ("Mantiq al-Tayr" by Attar) and when the birds seek a king, the hoopoe points out that the Simurgh was the king of the birds.

Hoopoes were thought of as thieves across much of Europe, and harbingers of war in Scandinavia. In Estonian tradition, hoopoes are strongly connected with death and the underworld; their song is believed to foreshadow death for many people or cattle. In medieval ritual magic, the hoopoe was thought to be an evil bird. The Munich Manual of Demonic Magic, a collection of magical spells compiled in Germany frequently requires the sacrifice of a hoopoe to summon demons and perform other magical intentions.

Tereus, transformed into the hoopoe, is the king of the birds in the Ancient Greek comedy The Birds by Aristophanes. In Ovid's Metamorphoses, book 6, King Tereus of Thrace rapes Philomela, his wife Procne's sister, and cuts out her tongue. In revenge, Procne kills their son Itys and serves him as a stew to his father. When Tereus sees the boy's head, which is served on a platter, he grabs a sword but just as he attempts to kill the sisters, they are turned into birds—Procne into a swallow and Philomela into a nightingale. Tereus himself is turned into an epops (6.674), translated as lapwing by Dryden and lappewincke (lappewinge) by John Gower in his Confessio Amantis, or hoopoe in A.S. Kline's translation. The bird's crest indicates his royal status, and his long, sharp beak is a symbol of his violent nature. English translators and poets probably had the northern lapwing in mind, considering its crest.

The hoopoe was chosen as the national bird of Israel in May 2008 in conjunction with the country's 60th anniversary, following a national survey of 155, 000 citizens, outpolling the white-spectacled bulbul. The hoopoe appears on the logo of the University of Johannesburg and is the official mascot of the university's sports teams. The municipalities of Armstedt and Brechten, Germany, have a hoopoe in their coats of arms.

In Morocco, hoopoes are traded live and as medicinal products in the markets, primarily in herbalist shops. This trade is unregulated and a potential threat to local populations.

Three CGI enhanced hoopoes, together with other birds collectively named "the tittifers", are often shown whistling a song in the BBC children's television series In the Night Garden....

Harrison Tordoff, a World War II fighter ace and later a noted ornithologist, named his P-51 Mustang as Upupa epops, the scientific name of the hoopoe bird.

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Category / Seasonal Status

BCST Category: Recorded in an apparently wild state within the last 50 years

BCST Seasonal statuses:

- Resident or presumed resident

- Non-breeding visitor

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Bucerotiformes

- Family

- Upupidae

- Genus

- Upupa

- Species

- Upupa epops

Common names

- Thai: นกกะรางหัวขวาน

Subspecies

Upupa epops africana, Johann Matthäus Bechstein, 1811

Range: Central Africa to South Africa. Much more rufous than nominate

Upupa epops ceylonensis, Heinrich Gottlieb Ludwig Reichenbach, 1853

Range: Indian Subcontinent. Smaller than nominate, more rufous overall, no white in crest

Upupa epops epops (nominate), Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

Range: NW Africa, Canary Islands, and from Europe through to south central Russia, north west China and south to north west India

Upupa epops longirostris, Thomas Caverhill Jerdon, 1862

Range: South east Asia. Larger than nominate, pale

Upupa epops major, Christian Ludwig Brehm, 1855

Range: North east Africa - Larger than nominate, longer billed, narrower tailband, greyer upperparts

Upupa epops marginata, Jean Louis Cabanis & Ferdinand Heine, 1860

Range: Madagascar. Larger, much more pale than U. e. africana

Upupa epops saturata, Axel Johan Einar Lönnberg, 1909

Range: Japan, Siberia to Tibet and south China. As nominate, greyer mantle, less pink below

Upupa epops senegalensis, William John Swainson, 1913

Range: Senegal to Ethiopia. Smaller than nominate, shorter winged

Upupa epops waibeli, Anton Reichenow, 1913

Range: Cameroon through to north Kenya. As U. e. senegalensis but darker plumage and more white on wings

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN3.1)

Photos

Please help us review the bird photos if wrong ones are used. We can be reached via our contact us page.

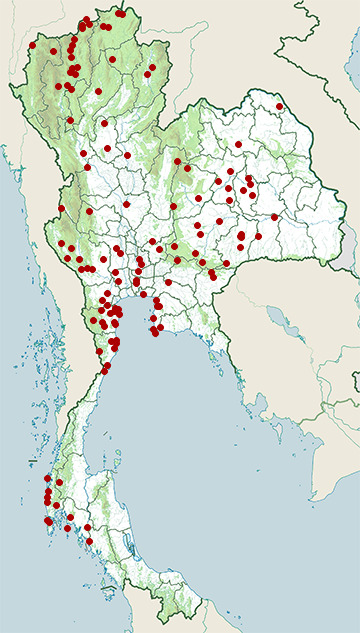

Range Map

- Ban Chang District, Rayong

- Ban Laem District, Phetchaburi

- Ban Lat District, Phetchaburi

- Ban Phai District, Khon Kaen

- Bang Lamung District, Chonburi

- Bang Pa In District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Bang Phra Non-Hunting Area

- Bang Pu Recreation Centre

- Bangkok Province

- Borabue District, Maha Sarakham

- Bueng Boraped Non-Hunting Area

- Bueng Khong Long Non-Hunting Area

- Cha-Am District, Phetchaburi

- Chiang Dao District, Chiang Mai

- Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Chiang Saen District, Chiang Rai

- Doi Inthanon National Park

- Doi Lang

- Doi Lo District, Chiang Mai

- Doi Pha Hom Pok National Park

- Doi Suthep - Pui National Park

- Don Chedi District, Suphan Buri

- Erawan National Park

- Fang District, Chiang Mai

- Hat Wanakon National Park

- Huai Chorakhe Mak Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

- Huai Krachao District, Kanchanaburi

- Huai Talat Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Kaeng Khoi District, Saraburi

- Kaeng Krachan District, Phetchaburi

- Kaeng Krachan National Park

- Kamphaeng Saen District, Nakhon Pathom

- Kantharawichai District, Maha Sarakham

- Khao Khiao - Khao Chomphu Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Lak - Lam Ru National Park

- Khao Nang Phanthurat Forest Park

- Khao Phra - Bang Khram Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park

- Khao Sanam Prieng Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Sok National Park

- Khao Yai National Park

- Khao Yoi District, Phetchaburi

- Khon San District, Chaiyaphum

- Ko Phra Thong

- Kui Buri National Park

- Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani

- Laem Pak Bia

- Lam Nam Kok National Park

- Mae Ai District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Ping National Park

- Mae Rim District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Taeng District, Chiang Mai

- Mancha Khiri District, Khon Kaen

- Mueang Buriram District, Buriram

- Mueang Chaiyaphum District, Chaiyaphum

- Mueang Chiang Mai District, Chiang Mai

- Mueang Chiang Rai District, Chiang Rai

- Mueang Chonburi District, Chonburi

- Mueang Kanchanaburi District, Kanchanaburi

- Mueang Khon Kaen District, Khon Kaen

- Mueang Krabi District, Krabi

- Mueang Lampang District, Lampang

- Mueang Maha Sarakham District, Maha Sarakham

- Mueang Nakhon Pathom District, Nakhon Pathom

- Mueang Nakhon Ratchasima District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Mueang Nan District, Nan

- Mueang Nonthaburi District, Nonthaburi

- Mueang Phang Nga District, Phang Nga

- Mueang Phayao District, Phayao

- Mueang Phetchaburi District, Phetchaburi

- Mueang Phitsanulok District, Phitsanulok

- Mueang Prachuap Khiri Khan District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Mueang Ratchaburi District, Ratchaburi

- Mueang Sukhothai District, Sukhothai

- Mueang Suphanburi District, Suphan Buri

- Mueang Surin District, Surin

- Mueang Tak District, Tak

- Nam Nao National Park

- Non Din Daeng District, Buriram

- Non Thai District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Nong Bong Khai Non-Hunting Area

- Nong Song Hong District, Khon Kaen

- Nong Ya Plong District, Phetchaburi

- Pa Sang District, Lamphun

- Pai District, Mae Hong Son

- Pak Chong District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Pak Thale

- Pak Tho District, Ratchaburi

- Pang Sida National Park

- Pang Tong Royal Forest Park

- Pha Daeng National Park

- Pha Hin Ngam National Park

- Phi Phi Islands

- Phimai District, Nakhon Ratchasima

- Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

- Pran Buri District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Pran Buri Forest Park

- Ratchasan District, Chachoengsao

- Rattanaburi District, Surin

- Sai Yok District, Kanchanaburi

- Sai Yok National Park

- Sakaerat Environmental Research Station

- Salak Pra Wildlife Sanctuary

- Samae San Island

- San Sai District, Chiang Mai

- Sanam Bin Reservoir Non-Hunting Area

- Sattahip District, Chonburi

- Si Satchanalai District, Sukhothai

- Sikao District, Trang

- Sirinat National Park

- Sri Nakarin Dam National Park

- Takua Pa District, Phang Nga

- Tha Yang District, Phetchaburi

- Thai Mueang District, Phang Nga

- Thalang District, Phuket

- Tham Sakoen National Park

- Thao Kosa Forest Park

- Thap Lan National Park

- Thong Pha Phum District, Kanchanaburi

- Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary

- Wapi Pathum District, Maha Sarakham

- Wat Phai Lom & Wat Ampu Wararam Non-Hunting Area

- Wat Tham Erawan Non-Hunting Area

- Watthana Nakhon District, Sa Kaeo